Artifacts turned into Time Team TV show and video game props with Artec 3D scanning

Challenge: Shadow Tor and the University of Plymouth were charged with digitizing rare finds, period clothing, and the Time Team crew for a TV series and upcoming video games.

Solution: Artec Leo, Artec Ray, Artec Space Spider, Artec Studio, Agisoft Metashape

Results: Creating Time Team avatars with Artec Leo rather than a photogrammetry kit turned a months-long process into one that took just a few days. Artec 3D scanning has also allowed rare finds and heritage sites to be digitized with incredible accuracy, so they can be preserved for future generations, and in future, explored in Virtual Reality (VR).

Why Artec 3D? The all-in-one wireless Artec Leo, complete with an intuitive built-in display, was the best possible tool for avatar digitization in remote areas. Faster and less obtrusive than using a photogrammetry booth, Leo delivered time savings of historic proportions.

In the world of archeology, the Time Team crew are probably as close to being celebrities as you can get. During the 1990s and 2000s, the team behind the much-loved British TV show brought the excitement of excavating historic dig sites to viewers across the country, and it has been aired in over 50 others since.

While the program ceased production in 2014, it has recently been revived in the UK as a YouTube series and on TV sets in the wider world, bringing in a new team of archeological enthusiasts to join the original cast.

Aiming to keep their content fresh in the digital age, the Time Team crew has set its sights on recreating how historic sites would have looked in 3D, through stunning TV show graphics, an interactive museum, and a VR video game series.

Time Team enters the digital age

To fulfill their ambitions of making history more engaging, Time Team has embraced advanced technologies via a partnership with the University of Plymouth.

Over the last ten years, the university has worked with Artec Gold-certified partner Patrick Thorn and Co on various projects, adopting the metrology-grade Space Spider in 2019, and upgrading its scanning capabilities by acquiring Artec Leo and Artec Ray a year later.

The Artec Ray 3D scanner set up outside a historic Dartmoor farmhouse site. Image: plymouth on Instagram

Now in the process of installing the largest video game lab in South Western England, Plymouth – the proud owner of an Artec Leo and Ray – is fast becoming a leader in virtual design.

Seeking to boost the career prospects of its students via commercial tie-ups, the University of Plymouth first agreed to start working with Time Team in 2022. Initially, the organizations set out to turn a historic Devon farmhouse into a virtual tourist attraction, as part of a collaboration with Time Team partner Shadow Tor Studios that would later progress into video game CGI.

For Plymouth lecturer Joel Hodges and Shadow Tor boss Matt Clark, collaborating was also a mini-reunion. Having first met Clark working locally as a 14 year old, Hodges knew of his expertise in the area. As such, Hodges saw the project as “a perfect match” for his university’s research goals and a great way to get his students real-life work experience.

Utilizing their combined expertise, as well as the AI-powered Leo and long-range LiDAR Ray scanner, the developers found they could rapidly create a lifelike model of the entire building.

Artec Leo being used to capture the finer details of the Dartmoor heritage site. Image: plymouth on Instagram

“In the building itself, there’s a long barn with a section for keeping animals,” said Clark. “With Leo, we could scan some of its rather strange features, it was so easy. It was also nice having this bright, white piece of technology next to a historic, dusty building in a muddy, wet, damp part of Cornwall. It looked quite cool.”

“We captured lots of little features. Ray did the interior and Leo captured door frames plus weird little carved notches and burn marks that referred to casting away demons.”

Creating Time Team avatars

Having successfully digitized the Devon log house, which later featured in a Time Team special, Hodges, Clark, and their students were then tasked with developing avatars for the show’s upcoming video games and interactive content.

However, there was an issue: presenters and crew only gathered for filming. As shows were largely filmed at remote dig sites, this ruled out the photogrammetry booths traditionally used to create video game avatars, due to changeable weather and logistical impracticality.

Then there’s data processing. Photogrammetry booths use dozens if not hundreds of cameras to take photos of people from all angles. But synchronizing data captured by these into a 3D point cloud can take much longer than with 3D scanning.

“Booths are very good, you can take the necessary pictures in milliseconds, but how long does it take to process the data?,” queried Patrick Thorn, Director of Patrick Thorn and Co. “As we saw in Artec’s recent body scanning webinar, the speed with which you can scan and sculpt the models of bodies now with Artec Leo and Studio is incredibly fast.”

“Another big plus is Leo’s built-in Wi-Fi,” he added. “As soon as you have an internet connection, you can upload scans to Artec Cloud, ready to be processed in Artec Studio back at base.”

These speed benefits were reflected in the Time Team avatar project, with an initial capture and processing session taking just a few days. Led by Plymouth lecturer and graphic designer Musaab Garghouti, the dev team have even been able to digitize presenters wearing period costumes made up of traditionally difficult-to-scan shiny surfaces like armor, so that players will be able to change apparel in-game.

According to Clark, Leo’s rapid 35 million point per second capture speed also made it easier to scan the crew without having to tell them: “stand still and don’t breathe for 20 minutes.”

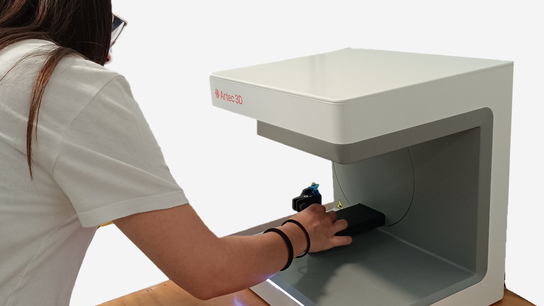

Shadow Tor’s Matt Clark with the Artec Leo 3D scanner

“For the people, the costume folds, the natural lighting, everything you’d want to match the footage for an episode was captured,” added Clark. “People don’t like to stand still for very long either, and on a filming schedule it’s rare they get a chance to anyway. Compared to taking 600 photogrammetry photos of someone’s head, Leo was so much faster to use.”

“I know you can get pop-up booths, but because our setup can be two hours from a road or power, 3D scanning is the only obvious way to do it.”

Making historical models

While Hodges and Clark exclusively used the wireless, AI-powered Leo to capture their Time Team avatars, they later incorporated photogrammetry into their workflow for digitizing props.

When it came to scanning shiny costumes such as Roman armor, the developers initially found that their reflective surfaces made them tricky to capture. With Artec Studio, however, it’s now possible to seamlessly combine 3D scanning and photogrammetry data.

Artec Leo’s built-in display being used to view the preview of a 3D scanned Roman costume

Using this functionality, the team have been able to fill any gaps in their models with high resolution camera photos, to achieve extremely high texture quality, and ultimately, develop incredibly lifelike digital avatars.

Artec Studio has also made it easier to export models into photogrammetry programs like Agisoft Metashape. In fact, with Artec’s software, they’ve been able to drastically reduce model poly counts and make them easier to render in-game, without losing any valuable texture data such as garment folds or the intricacies of historic props.

“We keep the high-poly faces, but to get the poly count down for gameplay and movement it has to be crunched,” explained Clark. “It also has to be crunched in such a way that the texture detail is baked-in first, keeping all that high-res scan material. We then put that back over the low-poly model to get solid, highly-detailed models.”

Plymouth’s expansion plans

With the University of Plymouth and Shadow Tor gradually making progress digitizing the Time Team crew, they’re now planning the next stage of their collaboration. At another dig site, they were previously able to digitize a roman sarcophagus as it was excavated.

It’s thought this kind of real-time captured footage could soon be used to create immersive TV experiences, and the team’s planning to return there imminently. In future digs, they also aim to use Leo, Ray, and Space Spider to create further video game props.

For Hodges, however, the impact of initiatives like its Time Team collaboration goes beyond what it’s possible to recreate as digital twins. His department has established partnerships with many leading video game developers, and these have led to a boom in demand for his University of Plymouth courses.

A chainmail costume being digitized with Artec Leo

As his department’s facilities continue to grow, Hodges therefore plans to roll out three new courses, designed to provide students with skills that better meet industry needs.

“Technical designers are becoming more in-demand, as studios want somebody who’s able to work in the editor, as well as being a game designer,” concluded Hodges. “We’re starting to bridge that gap now between engineering and design. In our new courses, we’ll have people work on 3D scanning, but then also work with an engineer to implement everything.”

“The avatar capture process is something that we’re going to continue to work into our curriculum, but the faculty is pushing towards more commercial collaboration.”

Scanners behind the story

Try out the world's leading handheld 3D scanners.