Using Artec 3D scanners to save all that could be saved from the world’s oldest civilization: Mesopotamia

Challenge: Over decades, the Iraqi people have faced bombing, war, and destruction – and the heritage that makes up the cradle of civilization has greatly suffered, too. The challenge here was to scan these lands as part of a film made by filmmaker Ivan Erhel.

Solutions: Artec Space Spider, Artec Eva, Artec Studio, Agisoft Photoscan (now Metashape) for photogrammetry, and drone scanning

Results: The film has been completed, and a new project has begun: teaching the youth of Iraq about 3D scanning technology while collectively digitizing the country.

Capturing data from high places demanded a bit of improvisation

The cradle of civilization, the birthplace of such essential tools as writing and recorded history – Mesopotamia. Yet for all the sanctity and value we would otherwise associate with a country that holds so much of the world’s cultural heritage, vast stretches of modern-day Iraq lie in ruin, with so much lost, damaged, or destroyed in war.

This project began with one idea: that it was essential to save what could still be saved.

“It all began in February 2015 over drinks at home with a friend of mine and my wife’s,” said French filmmaker Ivan Erhel. This friend had just bought an Artec Eva, a professional handheld 3D scanner, and he was crazy about it. “He wanted to scan the world,” Erhel recalled.

Having seen a video of ISIS destroying a museum in Mosul, both men were shocked. Erhel’s friend lamented how terrible it was that so much had already been lost.

“He said, ‘If I’d only been there a moment before,’” Erhel explained, “‘we would still have a good and precise image of what it was like. But now, it’s too late.’”

“We kept on talking and came to the conclusion that there was still a lot to protect in Iraq,” said Erhel. “I said, ok, let’s go for what’s left.”

Erhel was eventually left coordinating the project on his own, facing many challenges with getting a visa and obtaining the necessary authorization to start work. He soon realized that given all the other obstacles that would be encountered, it would make the most sense to continue with the project while centering it on what he knew best: making a film.

“I really wanted to do something – but I’m not military, I’m not a politician, I have absolutely no power,” he said, “But, I make films. So, I said, ‘Well, let’s make a film.’”

Jawad Bashara with archeologist Abdulameer Al Hamdani and photographer Sarmat Beebl headed towards the famed Ziggurat (Photo: Films Grain de Sable)

The story follows the journey of a man named Jawad from South to North. He is an Iraqi writer who had sought refuge in France and then returns to Iraq 35 years later with the intention of coming back to his country and doing what he can to preserve what’s left of the heritage that has been lost, and what remains – by using 3D scanning.

“The protagonist, he’s not a geek at all,” Erhel laughed. “But, he manages to handle the scanner and to scan in a professional way.”

And with this storyline, the team was able to do several things at once: make a film, 3D scan Iraq, and demonstrate the accessibility of 3D technology.

Scanning their way across the country

The first thing the team tried to scan was what remains of the Processional Way, a long brick road which once ran about 250 meters long and 20 meters wide. The Way was also adorned with more than 100 animals and legendary creatures, one of which (a mušḫuššu or mushkhushshu – a lion-dragon hybrid) was scanned. They also scanned a foundation brick of the wall commemorating the construction of the Ziggurat of Babylon, more commonly known as the Tower of Babel.

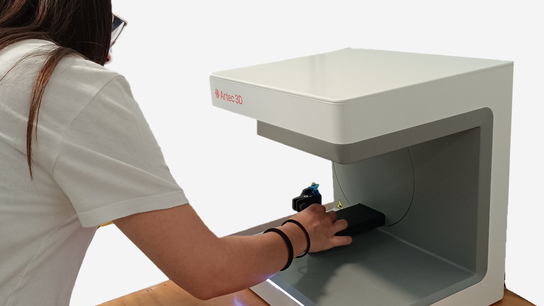

Scanning the foundation brick with Artec Space Spider

And given the struggles seen in these parts, the team had their work cut out for them when they arrived to start scanning. “In Nimrud, most of the bas relief was totally destroyed,” said Erhel. “In Babylon, the Mušḫuššu have lost their colors, but are in a rather good state of conservation as they were buried under the sand for centuries. And in Hattra, the site had been occupied by ISIS for several years and the sculptures had been "defaced" – meaning they had their faces erased with hammer or gunshots.”

When Erhel and the team he had assembled headed to Iraq in 2016, ISIS was occupying 30% of the country, Erhel recalled. “The situation was tense,” he said. “But we went back again, and again.”

For Erhel, Artec Space Spider was an ideal choice for use with a turntable when scanning small objects like a foundation nail or a brick which they were able to do indoors, in a calm environment. The Space Spider’s ability to render complex geometry, sharp edges, and thin ribs is what makes it an essential solution for small, intricately designed parts like these cultural relics, providing high resolution and the best quality scans when used on its own, or when paired with another scanner. On the field, Artec Eva was found to be most suited to the task, as it was less sensitive to uncontrolled movement when being held on a stick, and was able to analyze bigger objects like a bas relief with a wider angle.

The team was able to capture high places with Artec Eva while traveling through the country

For one monument, which was 60 to 75 meters wide and 30 meters high, a combination of Eva and Space Spider was used. Some scanning was also done with a drone – which was illegal in Iraq and as a result confiscated for a week – while other parts required the use of makeshift tools to help reach difficult areas.

“Always with a scanner on a stick,” he described, given that some parts were so high up they were difficult to reach, and it was impossible to move them.

Staying on the move, Erhel led his team from north to south, scanning everything from ruins to monuments to the faces of citizens and soldiers. “We scanned people, and when they could see themselves on the computer screen, they understood what we were doing,” Erhel said. “But then they would ask, ‘Why do you scan – Oh, to protect heritage? Oh, heritage! Well, we’ve got some here.’” he laughed.

“ISIS had started pushing north, so we were on the first non-military side of Nimrud,” he recalled. “Unfortunately, that was totally destroyed – with the exception of one sculpture.”

Naming this sculpture the Last Survivor of Nimrud, the team decided to begin scanning it with Eva – but at that very moment, gunfire was heard. “They shot into the air,” he said. “The militia was protecting the site, and they thought maybe we were looters.”

Once the true purpose of the team was explained, however, they were more warmly received, and the scanning was allowed to continue.

Preserving what could be digitally captured

Considering the cause

But with tension, destruction, and death ever present and in such close proximity, Erhel and his team were faced with a difficult question: Is it fair to focus on the preservation of heritage when people are being killed everywhere, and every day?

The answer came to Erhel through an Iraqi general in Mosul. “He said, ‘We’re like a tree’,” Erhel recounted. “‘When people fall, it’s like the falling of leaves and branches. But if you destroy the roots, then there is no tree.’”

That’s why it’s important to take care of these “old stones,” he realized, even amid war and suffering. “We kept moving on, following the army and the coalition, until Mosul was totally liberated in 2017,” he said.

Giving back what we owe

For this dedicated team, their work goes beyond cultural preservation; it extends to capturing the history that shapes the world we live in today. “Here is where they invented everything,” Erhel said. “Writing, the concept of law, scientific discoveries, trigonometry, math, architecture, the first arch (‘which we also scanned,’ he added) – Iraq is not just a country at war; it’s where Western civilization was born.”

While the movie is complete, the work and plans for Erhel and his team are far from over. Their next stop: A workshop in October called Tech 4 Heritage, where they plan to teach Iraqi youth about 3D technology in a far more educational and participative way. Erhel is currently planning meetings with Iraqi TV and French broadcasting for taking the project further, but for now the full 90-minute film will be aired on French and German TV channel Arte, after which a shorter 50-minute version will air in 20 more countries.

“I want to launch a movement of preserving heritage,” Erhel said. “If I teach 40 people how to use 3D, and they teach more people, and we start gathering data from all over the country, we can digitize all of it,” he said, adding that he is sending his Eva back to Iraq for common use “where it belongs.”

While much had already been lost, what is left can still be saved

“The country is super divided, but there is heritage everywhere in Iraq,” he said. “And heritage is something (or the only thing other than a football team, he clarified) that can bring the country together.”

And besides doing whatever he can to develop common ground in the country over a shared love of heritage, mobilizing the people to get involved, and giving something back to the youth – there is also a larger dream to restore some pride in Iraqi people for being the cradle of civilization.

Ancient relics can now be digitally captured, and made accessible to all

“At several points throughout history, Baghdad has been at the top of the world,” he said. “Perhaps now we can reunite the country a little bit, and also remind the world what we all owe to Mesopotamia – because 90% of our culture originates from here, we owe them everything.”

And while the 3D scanning work takes place all over this country, the documenting of such rich history can only benefit the entire world.

“This story is set in Iraq,” Erhel said, “but this history belongs to all of us.”

Scanners behind the story

Try out the world's leading handheld 3D scanners.