How 3D scanning helped reveal the face of the 3500-year-old Griffin Warrior

Challenge: As part of an ongoing excavation sponsored by the University of Cincinnati, an acclaimed UK facial anthropologist was called upon to digitally reconstruct the skull of an ancient warrior and create a painstakingly accurate approximation of his face as it had appeared in real life.

Solution: Artec Spider, Artec Studio, Geomagic Freeform, Abrosoft FantaMorph

Results: Each cranial fragment was scanned, along with groups of fragments, after which the skull was digitally reconstructed in Artec Studio software. From there, the 3D model was exported to Geomagic Freeform, where it served as a detailed reference model for creating the ensuing facial approximation, now ready for use online, for research, and 3D printing.

The digital facial approximation of the Griffin Warrior. Image courtesy of Dr. Tobias Houlton

For thirty-five centuries his body rested in a tomb beneath an olive grove just a short walk from the Palace of Nestor in southern Greece. Surrounding him were more than 2,000 objects dating back to the Bronze Age, including gold cups, rings, and necklaces, hundreds of precious gems, an ornate sword, and the breathtaking, intricately carved Pylos Combat Agate.

A gold-hilted dagger that had originally been resting upon the chest of the Griffin Warrior. Image courtesy of the Palace of Nestor Excavations, Department of Classics, University of Cincinnati

Given the name “Griffin Warrior” after an ivory plaque bearing the engraving of a griffin was found with him, this ancient Mycenaean nobleman’s true identity is still a mystery.

Drs. Sharon Stocker during the excavation of the Griffin Warrior’s tomb. Image courtesy of the Palace of Nestor Excavations, Department of Classics, University of Cincinnati

But while University of Cincinnati archaeologists Jack Davis and Sharon Stocker excavated his tomb over the course of six months, as soon as they discovered the mostly intact skeleton of the Griffin Warrior, they turned to the science of forensic facial approximation to see what he had looked like in real life.

Griffin Warrior grave excavation plan. Image courtesy of the Palace of Nestor Excavations, Department of Classics, University of Cincinnati

Biological anthropologist Prof. Lynne Schepartz and facial anthropologist Dr. Tobias Houlton were brought in to assist with this complex, multi-stage process. Schepartz led the excavation of the skull fragments, and Houlton focused on the skull reconstruction and face prediction of the Griffin Warrior.

As course coordinator and lecturer for the MSc in Forensic Art and Facial Imaging program at the University of Dundee, Scotland, as well as a forensic artist and expert in his field, Houlton has worked with Interpol and numerous police agencies in the UK and South Africa on various cases requiring facial approximation for victim identification.

His work has been recognized by National Geographic Magazine, the Smithsonian Channel, BBC Radio 4, and elsewhere.

Taking the right 3D scanner for the task

When it was time to travel to Greece, to begin the excavation and reconstruction of the Griffin Warrior, Houlton brought an Artec Spider along with him.

Artec Spider scans of the Griffin Warrior’s skull in-situ. Image courtesy of Dr. Tobias Houlton

A first-choice 3D scanner among forensic specialists and researchers around the world, the Spider is recognized for its abilities to non-destructively capture objects of all shapes and complexities, with submillimeter degrees of accuracy, even those with otherwise-challenging features, such as cranial sutures, wafer-thin bone fragments, etc.

In Houlton’s words, “I knew that the Spider would fit in perfectly with my workflow. Instead of having to adjust everything to meet the needs of the technology, which is what happens with many solutions, Spider was right there with me at every step.”

The digitally reconstructed skull of the Griffin Warrior in Artec Studio software, image courtesy of Dr. Tobias Houlton

“Before I lifted a cranial fragment from the sediment, I would scan that layer, in order to preserve each fragment’s exact location and orientation within the sediment.”

He continued, “Then I would scan each piece again, right after excavating it, and would also temporarily glue together groups of fragments and scan these. That way, when it came time to digitally reconstruct the skull, the Spider scans provided precise digital twins of these skull fragments, not to mention the original in-situ scans, which from an archaeological point of view are indispensable.”

CT scanning through ancient soil

But before that could take place, the block of sediment containing the Griffin Warrior’s remains was extracted from the site and brought to the lab. There, a CT scanner was used, to try and distinguish any skeletal elements from the other objects around them.

Unfortunately, the CT wasn’t able to differentiate bone from the other objects in the sediment, yet at least it provided a map of object locations, which later proved useful while extracting the Griffin Warrior’s skeletal remains.

Houlton’s scans were done directly within Artec Studio software, with each scan taking around one minute or less for full capture of individual cranial fragments and sediment layers.

Following this, the scans were processed into 3D models, and what’s more, because Geomagic Freeform wasn’t accessible to Houlton at that moment, he fully reassembled the Griffin Warrior’s skull in Artec Studio.

According to Houlton, “Artec Studio’s alignment tools made it easy for me to select specific fragments, move them around, and align them properly in relation to all the other pieces. It didn’t take long for me to reassemble everything and finally obtain a digitally reconstructed version of the Griffin Warrior’s skull.”

When traditional casting is too risky, 3D “digital casting” is ready to help

Reflecting back on traditional casting methods for documenting skeletal remains, Houlton said, “In the case of the Griffin Warrior, many of the skull fragments were so fragile that there would have been no way for us to safely cast them.”

He elaborated, “Yet Artec Spider ‘digitally cast’ each one in just seconds, and now we have protected 3D copies of them, without ever damaging or posing any danger to the original objects.”

Once back at the office, Houlton exported the digital twin of the Griffin Warrior’s skull from Artec Studio over to Geomagic Freeform, for the actual facial approximation.

Freeform: first choice for digital skull reconstruction and facial approximation

With the software’s ability to put the reconstructionist in direct kinesthetic contact with the 3D object via a haptic pen interface, Freeform is an ideal tool for anyone doing the work, from student to accomplished practitioner.

Geomagic Freeform screenshot showing the Griffin Warrior’s skull ready for facial approximation. Image courtesy of Dr. Tobias Houlton

Unlike traditional clay facial approximations, Freeform makes it possible to share the entire approximation with agencies or digital artists near and far, in seconds from the time of completion.

Even more consequential is the guarantee that with digital approximations, in contrast with clay, there’s no danger of the original ever being damaged or lost.

Expanding upon this, Houlton said, “Now, once we’re done with an approximation in Freeform, if the original skull is ever lost or destroyed, and if there’s ever any question about the accuracy of the predicted face, all it takes is referring back to the Spider scans of the skull.”

Geomagic Freeform screenshot showing the Griffin Warrior’s facial approximation underway. Image courtesy of Dr. Tobias Houlton

“Within seconds, you’ll be able to verify, without even a glimmer of doubt, the accuracy of the skull reconstruction. Because when you’re looking at the Spider scans, it’s as close to looking at the real skull as anything else,” he said.

Houlton shares with his students at University of Dundee his full spectrum of insider workflow tips and tricks with Freeform.

So, whether they’ll eventually find themselves working as facial approximation practitioners in cooperation with police or intelligence agencies, or as CGI specialists immersed in the world of film, TV, or video games, they’ll have all the foundation they need to transform Artec 3D scans into stunningly lifelike facial approximations.

Rebuilding the face of the Griffin Warrior in Freeform

Since several of the Griffin Warrior’s thinner facial bones were missing, specifically those around the nose, as they’d disintegrated over time due to the acidic soil conditions at the grave site, Houlton relied on his own approach to accurately fill in the gaps.

He created an average face template from the images of 50 faces of modern Greek men of similar age and build, and then brought them together in Abrosoft FantaMorph. Facial averages identify consistent trends in facial patterns, which supported Houlton with the remaining approximation where individual details cannot be ascertained.

In Geomagic Freeform – using the tissue depth markers to help build the Griffin Warrior’s face. Image courtesy of Dr. Tobias Houlton

During the approximation, Houlton first inserted the eyes, then all the tissue depth markers (up to 36), followed by the muscles and the skin layer. Freeform’s ability to let users organize and label all these features as independent objects and store them in their own folders is highly useful during facial approximation.

The Griffin Warrior’s face reborn: from digitally reconstructed skull to final facial approximation. Video courtesy of Dr. Tobias Houlton

As well, the software’s ability to “see through” the model and down below the skin, ensuring that soft and hard features relate to each other, saves the digital practitioner from what manual modelers must regularly endure: physically cutting into the clay/modeling wax to check with the underlying skull cast.

Why 2D photography should never be the first choice

When asked to compare working from 2D photographs versus 3D scans for facial approximation, Houlton commented, “2D photos should be a last resort. To give you an example why they’re not desirable, it’s very hard to gauge how deep the fossae are around the canine area, which in part indicates the form of the nasolabial folds.”

He continued, “In general, when it comes to accuracy and vivid realism, 3D scanning lets you achieve fantastic results compared to what you can do with 2D photos.”

In fact, the breadth of precise surface data provided by the Spider scans is more than sufficient for performing reconstructions directly from the scans, without having the original skull present as a reference model.

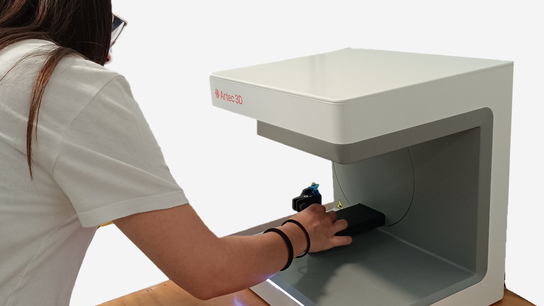

Dr. Tobias Houlton scanning a cranial fragment with Artec Space Spider at the University of Dundee. Image courtesy of Dr. Tobias Houlton

Houlton has done that very thing in multiple international projects over the years. “Having 3D scans of this degree of accuracy makes it possible to take on facial approximation work without ever having to leave our offices.”

Whenever the need arises for a physical model of an approximation, whether for investigative, legal, or other purposes, it’s a simple step to export the digital approximation for 3D printing.

In practice, this can mean finishing a facial approximation, sharing the 3D model with the client, who receives it seconds later, even on the other side of the world. Then they begin reviewing it on-screen while 3D printing a physical model, ready for use just hours later.

3D scanning & 3D printing in human anatomy education

At the University of Dundee’s Digital Making facility, with its collection of 28 various 3D scanners, Houlton and his students have been 3D printing their Spider scans, along with scans from Dundee’s other Artec scanners: Eva and Space Spider.

The successor to Spider, Space Spider features all the power of its predecessor, in addition to powerful temperature stabilization and high-grade electronics.

The Artec Space Spider

Dundee’s MSc Forensic Art and Facial Imaging program adopted Artec scanners as part of their curriculum years ago, after being introduced to them by Artec 3D Gold Partner Patrick Thorn.

A highly experienced specialist in 3D scanning for education, cultural heritage, forensics, healthcare, and beyond, Thorn endeavors to understand the needs of his clients, to help them integrate the very best solutions possible. He also conducts workshops for his clients in numerous locations across the U.K., from the tip of Cornwall up to northern Scotland.

Lifelike 3D-printed bone and skull models in the classroom

Houlton commented on how essential 3D printing has been for teaching human anatomy at Dundee, saying, “We regularly work with 3D prints of skulls and other bones, since physically handling these models is immensely conducive to the learning process. And this is another area where our Artec scanners have proven useful.”

He continued, “For example, if you take some 3D-printed cranial anatomy made from Spider scans and set it side-by-side with a 3D print of the same piece of skull, yet made using scans from other 3D scanners we’ve tried, you can see a massive difference in terms of detail, accuracy, and realism.”

As explained in a previous case study, the University of Dundee continues to expand its work with 3D scanning and printing with each passing semester.

For the medical and forensic art students there, by the time they graduate, they will be fully capable of picking up an Artec 3D scanner, capturing any of the human body’s 206 bones in minutes, then transforming those scans into lifelike 3D models ready for AR, VR, 3D printing, or facial approximation in Freeform.

Facial decomposition, documenting mass graves, and beyond

Houlton’s latest project will take him to South Africa with the University of Witwatersrand. There he’ll be working with a PhD student and academic team on a project dedicated to researching the effects of decomposition on human faces, identifying the degree of changes taking place post-mortem, to understand what this means for facial recognition.

Following this, Houlton is hoping to embark upon an archaeology-based project with the Orkney Research Centre for Archaeology, working locally as well as throughout various countries/regions of Africa, engaging with documentation of mass grave sites.