Can Artec scanners capture objects through glass?

Challenge: To test the ability of Artec scanners to capture objects through glass, by digitizing the fragile remains of a creature from the Ice Age, which would extend the local city’s heritage by at least 12,000 years.

Solution: Artec Leo, Artec Studio

Results: A 200,000-polygon, fully textured, high-resolution 3D model of a Neosclerocalyptus for the regional museum’s digital archives, ready to be shared with the wider scientific community and the general public.

Artec 3D scanners have found use in a variety of scenarios, providing the ideal solution in countless workflows across many industries. These devices include scanners that can capture objects in broad daylight, scan directly to the Cloud, are fully wireless with a built-in computer, and can even be remote-controlled via a web browser.

With Artec Cloud, Artec’s real-time collaborative platform, it is also possible to upload, download, import, export, view, comment on, share, and process 3D scan data. The list goes on and on. The sizes of objects that Artec scanners can capture include everything from a fingernail-sized iPhone SIM card tray all the way up to a massive cargo ship.

Given their unique versatility, there are many questions about what else the scanners are capable of – in what other situations can these devices perform? Since all Artec scanners are able to capture objects without the need for targets, one question that keeps cropping up is whether or not scanning through glass is a possibility.

There are, it seems, quite a few cases where it is in fact the only option. For example, if you need to digitally capture museum artifacts. Or when you must scan an object through a window, which is sometimes called for during crime scene documentation.

Disegno Soft, one of our certified partners in South America, picked up on the interest in this, and decided that it was better to show how it could be done, not merely talk about it. In doing so, they’ve brought a story to light that enriches an entire city’s heritage. The city in question is San Francisco, Argentina. The story itself delves into the history of, oddly enough, armadillos.

San Francisco is a city that sits right at the eastern edge of the Cordoba province in Argentina. This puts it in the Pampas lowlands of South America – expansive plains covering more than 1,200,000 square kilometers (460,000 square miles).

Crucially, the area’s water sources are few and far between, so the region is thought to historically have been largely devoid of animals and human habitation. So, in the mid-90s, when construction workers unearthed the bones of many different prehistoric animals, the find was a bit of an oddity.

Excavation of the remains in San Francisco, Argentina. (Image courtesy of The Graphic Archive Foundation and Historical Museum of the City of San Francisco)

Among the discovered fossils was that of an extinct animal from the armadillo family called a Neosclerocalyptus. The Neosclerocalyptus is a glyptodont, a group of animals that is said to have fascinated the Father of Evolution himself, Charles Darwin.

This particular discovery was special because it included a more or less intact skull, making it a rare find. Alberto Orellano, from the Regional Graphic Archive and Historical Museum in San Francisco, talks about the exciting discovery:

“We were fortunate to retrieve more than 30 fossil remains, but the Neosclerocalyptus was the first one. We discovered it in a strange place – at the intersection of highways 19 and 158 … in an excavation site where different species, both carnivorous and herbivorous, were unearthed.”

For the city of San Francisco, the discovery is something to be especially proud of. San Francisco’s recorded history starts in 1886, with the founding of an immigrant settlement. It would be declared a city a few decades later, in 1915.

Not much was known about the history of the area before that time. But with this one discovery, a city whose history book goes back about 200 years can now add a 12,000-year-old entry to its pages.

The Graphic Archive Foundation and Historical Museum of the City of San Francisco and the Region, as it’s formally known, has a stated mandate of recording and preserving historical finds in the area. In Orellano’s words, “Our main focus is to rescue, study, and promote the History of San Francisco, Córdoba, and its region, the Argentine Republic.”

The Graphic Archive Foundation and Historical Museum of the City of San Francisco and the Region is responsible for the preservation and promotion of the region’s heritage. (Image courtesy of Disegno Soft)

Collaborating with the team of 3D scanning specialists at Disegno Soft on this project was therefore an exciting prospect for everyone involved. On one hand, there was the important task of preserving a city’s cherished heritage, and on the other, the opportunity to finally carry out a much-awaited test to see how Artec scanners would stand up to the scanning-through-glass challenge. Artec Leo was the scanner chosen for the task.

Artec Leo is an award-winning scanner, one of the fastest on the market. It is unique in its ability to offer a fully mobile, cable-free scanning experience, without the need for an external computer.

The Disegno Soft team with Alberto Orellano at the Graphic Archive and Historical Museum of San Francisco and the Region. (Image courtesy of Disegno Soft)

Leo features onboard, automatic processing, a touchscreen that builds a real-time replica while you scan, a built-in battery, and wireless connectivity that gives you the power to stream video to a second device. Leo can be remote-controlled, and can scan directly up to Artec Cloud.

For this particular project, Leo’s large field of view – and its ability to 3D scan and process objects and scenes quickly and accurately – made it the ideal choice. Leo also has its AI-powered HD Mode, which provides even sharper, cleaner, and more detailed scans.

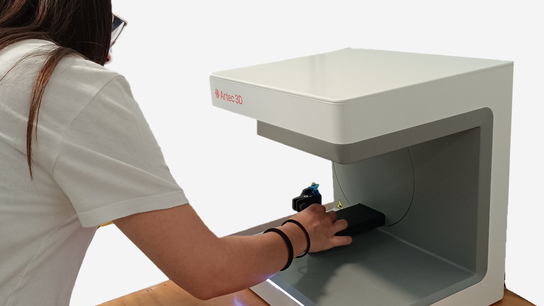

Scanning the Neosclerocalyptus fossil through its glass enclosure. (Image courtesy of Disegno Soft)

The Disegno Soft team went down to the museum and put the scanner through its paces. Even when working through glass, the scanning process itself was characteristically painless, taking only about 20 minutes. Processing and post-processing required extra time.

Processing was done in Artec Studio and involved alignment, removing the visible edges of the glass box, and erasing any noise present. The 3D model was then exported to SOLIDWORKS Visualize for post-processing and rendering. In total, the entire process took about 4 hours, from start to finish.

Alignment in Artec Studio during processing.

In general, there are several caveats when scanning through glass. There may be a loss of quality depending on several factors. The clarity of the glass, lighting conditions, and reflections off the glass. How refractive the glass is, as well as the distances between the scanner, glass, and object, also come into play.

In this particular case, the scan produced a model that meets the needs of the museum. What’s more, the final model is a great demonstration of the Artec Leo as a highly-versatile 3D scanner. The crucial details of the original specimen are preserved in the 3D model, and the scan’s texture also accurately reflects the original colors of the object.

The 3D model will go a long way towards efforts to preserve San Francisco’s heritage. Before Artec Leo was brought in, the museum’s exhibits were limited to photographs, documents, and specimens of historical objects and paleontological artifacts. The addition of 3D models is a welcome step up.

“Before using Artec Leo, we couldn’t create 3D models or share them with other museums or experts. Now that we have Leo, we can also replicate fossils and make the exhibition more interactive and attractive for visitors,” Orellano adds.

Scanners behind the story

Try out the world's leading handheld 3D scanners.